|

by Craig Kaczorowski |

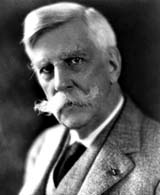

enry James "jacked off" Oliver Wendell Holmes? Who would have thought, even at this late date in the 20th Century, we would be thinking such thoughts? Both Henry James and his penis have been receiving considerable attention in the media lately which must make, one can only imagine, poor dear dead Harry stammer and blush in the grave. While Hollywood attempts to turn Mr. James into this yearís Jane Austen [with the somewhat critically and commercially successful film version of Jamesís Portrait of a Lady, several other of his novels have threatened to appear soon at the local multiplex], his biographers have taken it upon themselves to debate and hypothesize [some might call this "semi-invent"] his sex life. They are shameless, and surprisingly zealous, these biographers, turning themselves into public prosecutors searching for semen stains in Jamesís underwear, so to speak. enry James "jacked off" Oliver Wendell Holmes? Who would have thought, even at this late date in the 20th Century, we would be thinking such thoughts? Both Henry James and his penis have been receiving considerable attention in the media lately which must make, one can only imagine, poor dear dead Harry stammer and blush in the grave. While Hollywood attempts to turn Mr. James into this yearís Jane Austen [with the somewhat critically and commercially successful film version of Jamesís Portrait of a Lady, several other of his novels have threatened to appear soon at the local multiplex], his biographers have taken it upon themselves to debate and hypothesize [some might call this "semi-invent"] his sex life. They are shameless, and surprisingly zealous, these biographers, turning themselves into public prosecutors searching for semen stains in Jamesís underwear, so to speak.

James didnít make it easy for these future biographers, however. As he wrote, shortly before his death, in a letter to his nephew, " My sole wish is to frustrate as utterly as possible the post-mortem exploiter -- which, I know, is but imperfectly possible. Still, one can do something ... that is to declare my utter and absolute abhorrence of any attempted biography or the giving to the world ... of any part or parts of my private correspondence." He then made a bonfire of some 40 yearsí worth of accumulated memorabilia: letters, journals, manuscripts, notebooks. Friends and family had also agreed on their part to destroy all the letters he had sent them, but most didnít keep their side of the bargain. James was an inveterate gossip and energetic letter writer, and at least ten thousand of his own letters have survived. For some 40 years the life of Henry James was a cottage industry for the singularly obsessed Leon Edel, writer of the immense, and exquisitely composed, five-volume Life of Henry James published in the 1950s and 1960s. Edel had a pythonís hold on Jamesís private documents, with polite acquiescence from the literary executors of Mr. James and the hallowed librarians at Harvard University where most of the remaining letters and journals are kept. In fact, until just recently wild-eyed historians could still find folders in Harvardís stacks marked with red warning signs "Reserved for Leon Edel." Har-umph! After Edelís multi-volume biography, and the one-volume abbreviated version [for those readers who werenít all that interested in James], as well as the selected letters, the complete tales, the complete plays, the annotated grocery lists, etc., it seems Edel ran out of things to write about [and the time to write; he is now in his 90s], and loosened his grip on the short hairs of Henry. Those wild-eyed historians rejoiced and several new upstarts have found employment in the James factory. Within the past several years, assorted Jamesiana have appeared on the market, most notably Henry James, The Imagination of a Genius: A Biography by Justin Kaplan, and Sheldon Novickís Henry James, The Young Master. Kaplanís biography, disappointingly, is little more than rehashed and boiled down Edel. Whereas Edelís Henry James is asexual, shy, and somewhat scatterbrained -- a favorite maiden aunt, letís say -- Kaplan emphasizes the social climbing James, a Henry James interested in money, in business, in power, and in sex -- well not sex, exactly, just a lot of imagining it. However, reading between the lines of a more polite Edel, writing in more polite times, we could have guessed that already. Novick, on the other hand, obviously looking for a unique and sexy spin to put his biography in the public eye, has decided to repaint the portrait of James entirely, has decided that James was quite actively sexual, indeed that he was quite the gay blade, as it were. Novick has taken the stance, in his book and in post-publication interviews, of the young Turk beating up on an old fart. He accuses Edel of repressing "independent scholarship with legendary vindictiveness," and of "lashing out" in an "undignified way at every potential rival." Not only does this seem wrong-headed, but somewhat distasteful as well. You long for someone to ring up and say "For Christís sake, leave the old guy alone, will you." But Novick gallops on, claiming, by his book, to "overturn half a century of scholarship"--bad scholarship, on can only imagine he means.

But perhaps equally as important for our little colloquy here, Holmes was also the future subject of a biography written by one Mr. Sheldon Novick. One suspects Novickís interest in Jamesís interest in Holmes is perhaps driven more by the marketplace than by scholarship. Calling James actively queer may bring attention to his new biography, and saying James was actively queer with Holmes may bring attention to his other biography. Now thereís a marketing tie-in to rival anything ever cooked up by Disney. But Holmes is not the only fuck buddy Novick claims James had. Novick also makes some vague, muddy hints that James was friendly, in a sexual sort of way, with Paul Zuhkovski, a Russian aristocrat and Turgenev groupie that James met while living in Paris in 1876. Novick bases this claim on the fact that James and Zuhkovski kept up a steady friendship for some twenty years, a friendship maintained mainly through the writing of letters. James found the Russian "picturesque" and the two men swore an "eternal fellowship." Edel quickly disposes of this new claim, by saying "one could read sex into this" if one wants to [and Novick certainly wants to], but "it sounds more like the ... swagger and Ďbrotherhoodí" that "often takes place among young males." Even calling it "swagger" seems to be reading too much into the whole Zuhkovski affair. Unfortunately, Novick doesnít tell us what Harry and Paul did in bed or which positions they liked best. Itís a pity, but we must remind ourselves that this is only the first volume of Novickís Life Of James, which he ends in 1880 [with the publication of Portrait]. Maybe weíll learn more about Mr. Zuhkovski, and all the other lads who had flings with Mr. James, in volume two.

Edel, for his part, seems to quietly assume that Henry was impotent, and thus, celibate. Edel even quotes an British doctor who once examined James and determined that the writer had a "low amatory coefficient." What the heck is that supposed to mean? Assume it means that James was Princess Tiny Meat, and probably not very popular at the Anvil. Thankfully, neither Novick nor Kaplan have seen it necessary to force James to whip it out on the table and measure it with a ruler. Edel blames Jamesís impotence on the "obscure hurt" James often suffered and wrote about. The "obscure hurt" in question was a strained back James experienced during a stable fire while he was serving as a volunteer fireman during the Civil War. But we all know, from the precedent set by Jack Kennedy, that even a bad back canít keep a good man down. Of course, Novick has his opinions on Jamesís supposed celibacy as well. "James repeatedly described celibacy ... as a perversion when voluntary, and a living death when not." Novick says he has found "no evidence" of Jamesís supposed celibacy [just as others have found no evidence for Novickís certain claim of Jamesís supposed gayness]. Kaplan, feeling left out in the cold, throws in his opinion, and you have to admire his clear-eyed view of the whole damned thing. Kaplan doesnít think sexual agendas are the kind of thing one should "take for granted" about anybody. He is certain, however, that James "loved" some men, but he doesnít really know that that means, exactly. Opines Kaplan: "James was a fastidious man with a strong homoerotic sensibility." [Note that word "fastidious." I guess that means James had good grooming habits or a fine fashion sense, which I guess means he was gay.] What Kaplanís not certain of, however, is how Novick can claim that James did anything, especially wanking off Wendell Holmes. James may have, or he may have wanted to, but Kaplan agrees with Edel that "there isnít any credible evidence to support a claim that he did." Kaplan rightly realizes that it just is not very likely that we will ever know, that new evidence is not likely to turn up, that there just isnít a four-page nude photo spread in the North American Review with James and Holmes having it off. What baffles Kaplan, and curious others, is why Novick seems to think that James "would somehow be lesser, even diminished, if hadnít fucked or sucked or whatever with someone." [Those are Kaplanís own words, and somewhat overheated words, considering heís discussing Henry James and not Henry Miller. James would surely be appalled.] About the best one can do concerning James and his sex life is hope. As Millicent Bell recently wrote in the Times Literary Supplement, "One cannot help hoping, for Jamesís sake, that his life was not altogether devoid of sensual satisfaction." Before we make any hasty judgments of our own, letís take a look at the passage Novick uses as proof of Jamesís naughty doings with Holmes. Hereís James writing in his journal sometime in 1905, making notes for a book and reminiscing about his glory days in the spring of 1865:

"The point for me (for fatal, for impossible expansion) is that I knew there, had there, in the ghostly old C[ambridge] that I sit and write of here ... líinititation premiere (the divine, the unique), there and in Ashburton Place ... Ah, the Ďepoch-makingí weeks of the spring of 1865! -- from the 1st days of April or so, to the summer ... Something -- some fine, superfine, supersubtle, mythic breath of that may come in perhaps in the Three Cities, in relation to any reference to the remembered Boston of the Ďprime.í Ah, that pathetic, heroic little personal prime of my own ... that of the Seven Weeksí War and of the unforgettable gropings and findings and sufferings and strivings and play of sensibility and of inward passion there. The hours, the moments, the days, come back to me -- on into the early autumn before the move to Cambridge and with the sense, still, after such a lifetime of particular little thrills and throbs and daydreams there. I canít help, either, just touching with my pen-point (here, here, only here) the recollection of that (probably August) day when I went up to Boston from Swampscott and called in Charles St. for news of O.W.H. [Oliver Wendell Holmes], then on his 1st flushed and charming visit to England and saw his mother in the cold dim matted drawingroom of that house (past, never, since, without the sense), and got the news of all his London, his general English, success and felicity, and vibrated so with the wonder and romance and curiosity and dim weak tender (oh, tender!) envy of it, that my walk up the hill, up Mount Vernon St., and probably to Atheneum was all coloured and gilded, and humming with it, and the emotion, exquisite of its kind, so remained with me that I always think of that occasion, that hour, as a sovereign contribution to the germ of that inward romantic principle which was to determine so much later on (ten years!) my own vision-haunted migration." Well, obviously something happened around 1865, but what? James doesnít seem comfortable even letting his journal in on the real news -- note the "for fatal, for impossible expansion." He just isnít comfortable talking about whatever it was that happened, but he sure seems to like thinking about it. It makes him feel all warm and tingly down there. And Wendell Holmes seems to play some special part in this memory. James also canít help "just touching" with his pen-point [Dr. Freud call your office] "here, here, only here" the recollection of visiting Mrs. Holmes for news of her sonís virgin trip to Europe. Maybe James did it with the mother while the maid went to market? Edel seems to think that in this journal entry James is writing "generally about the Ďrite of passageí that inaugurated his literary career." Edel thinks that this entry had nothing to do with sex whatsoever, but about Jamesís first book review in the North American Review, whose editors paid him $12, and about the overwhelming emotions James felt when he heard that Hawthorne had died. Edel admits that James does mention Holmes, but only to describe a visit he made to Holmesí mother to ask how her sonís trip to England was and Jamesís "own fierce envy of Holmes for traveling abroad while James remained at home." Certainly nothing dirty in any of that. But even this seems too simple an explanation. Read the entry again. The words James uses are highly charged, intense, almost ardent. Even James, in his most ornate style, would not use such a tone to describe having a manuscript, even his first manuscript, accepted for publication, or the European sojourns of a friend, as a "fine, unique" experience that would be "fatal, impossible" to recall in his journal. Of course, we donít know exactly what James was writing about. And we never will know. Many of Jamesís stories and novel are simply tremulous with sex, but what the source of that was in Jamesís life weíll never precisely know. And frankly, it doesnít seem to be that important. Sure, weíd like James to be some leather-jacketed stud whose life was led by his crotch, but we are talking about Henry James here. But gay or straight, top or bottom, active or celibate, James is still a faultless artist, the best novelist America has yet produced. As to whether he "fucked or sucked" [Kaplan] or "jacked off" another man [Novick], weíll let Henry speak for himself: "Never say you know the last word about any human heart." |

| Table of Contents |

| Tension | February/March 1997 |

|